Last week, we looked at the quantitative characteristics of an elite team. Let's examine what qualitative characteristics an elite team has that enable them to make these numbers.

Behave like founders

If you look at the difference between how founders behave and how employees behave, there's a very distinct difference — ownership. Ownership here doesn't refer to the amount of stock you own. Rather, ownership here refers to the boundary of your responsibilities. Unfortunately, most employees view the boundary of responsibilities as directly proportionate to the amount of stock you own. To some extent this is true. A founder's responsibilities span not just the business, the employees, and the investors, but also the customers and, if highly successful, the societal moral expectations. An employee's responsibilities are bounded by the role she plays.

For an employee, the bigger the company, the narrower the responsibilities. Sadly, this is precisely what leads to underperformance. When an engineer faces an obstacle, the debate focuses on whose responsibility it is to complete the task as opposed to completing the task. Imagine if you're the sole founder and employee of your startup. In the same situation, you'd have no one else to turn to but yourself.

Because the buck stops with you when you're the founder.

You could argue an employee is not as incentivized to behave like a founder because of the disproportionate difference in stock ownership. But the founder had been building the company without a salary for months or years before she finally got funded (after hundreds of VC rejections) to hire you. If you can do the same, you should be a founder. But if you choose to be employed, you don't have as much leverage to argue for more stock. That's how negotiation works.

But if you're arguing about how you should behave based on the amount of stock you own, then I suggest you ask a deeper question, "Is there a place or job where you'd behave like a founder irrespective of the stock you own?" Because that is the job or place that will make you the happiest. It could be a group of people you admire. A role you're under-qualified for. Or even a hobby in a completely different field that is really your passion.

My point here is not that you shouldn't negotiate for more stock. Rather, how you behave shouldn't be based on the stock you own. Because your behavior defines you as a person. Not the stock. Once you can decouple your behavior from compensation, you'd price yourself right. Your negotiation becomes "For the quality of service you get from me, this is what it costs. If I were a neurosurgeon, would you pay me less for a lower quality of service?"

It is crucial to reflect on why we limit our potential based on our compensation. It's a fundamental misconception of cause and effect.

You're compensated for your behavior. Not the other way around.

It is this fundamental misconception that separates the elite from the rest. Once you can get past this, working with an elite team is incredibly rewarding. In an elite team, every team member thinks and behaves like a founder. The team is fully autonomous and self organized. Present the team with a problem and the team will solve the problem. Each team member owns her task end-to-end. When faced with a hurdle, she chases down the person who can remove the roadblock and ensures the task gets completed with urgency. Without prompting from anyone. Because no one manages the founder.

Like a founder, every elite team member is proactive. She anticipates everything that needs to be in place for her to ship a feature. If there's a missing specification in the UX, she'd get clarification from the product owner before heading into grooming. If a mockup is missing, she chases that down before the work is pulled into a sprint. If a security group needs to be adjusted, she follows up with DevSecOps to get it done.

"It's not my job" doesn't exist in her vocabulary.

Ship relentlessly

I first came across this phrase on Honeycomb Value and fell in love with it. Shipping relentlessly is the hallmark of an elite team. The desire to ship overwhelms the desire for perfection.

Shipping > Perfection

Perfection is a mirage. If you pursue it, death will precede. Perfection leads to paralysis and missed opportunities. An elite team understands this. Speed is the biggest advantage a startup has over incumbents. So, you ship first and iterate after. But this doesn't mean you neglect your craft. Because you are always short on time, you need to focus on what really matters. You ship the most critical functionalities first because they are most valuable to customers. What you ship may even be inconvenient to use. But that's okay. The ability to ship quickly allows you to improve the UX incrementally. This yields a few benefits:

- Gives you a leg up on your competitors because you are first to market. You could be the category leader. In certain industries, that could mean everything.

The category leader wins the easy sales — the order taking — while also-rans must sell hard to win every deal.

- David Sacks

- The customers get to benefit (or not) from the basic feature you just shipped. Either way, you get feedback that will inform the decision on further investment or cause changes to the current design.

- Getting basic functionality into the hands of customers within hours is a huge morale boost for the team. According to Google re:Work, meaningful and impactful work are 2 of 5 important factors that lead to high performing teams.

A high frequency, consistent shipping cadence is the lifeblood of an elite team. Missing the cadence is synonymous to stopping an assembly line. It's disheartening. But understanding the impact of the inability to ship, the team would promptly investigate and address the root causes. When the team can't ship, lead time increases and deployment frequency drops. An elite team has seemingly infinite grit and is relentlessly resourceful. There is a collective sense of superiority such that no problem is ever too difficult to solve.

Accountable

One of the most rewarding aspects of working with an elite team is you get full autonomy. The reason for the autonomy is so the team can make decisions rapidly, unencumbered by elaborate committee approvals. According to the DORA report, companies with > 5,000 employees tend to have elaborate change approval processes. This is one reason why larger companies tend to have lower performing teams (though there are well known exceptions). But with the freedom to exercise judgement comes the accountability for the consequences resulting from the actions or inactions.

Autonomy and accountability are two sides of the same coin.

Therefore, nothing’s more demotivating than robbing a team of its accountability. When a team fails to deliver (it happens even with an elite team), don’t deny the team its opportunity to recognize the mistakes made and the opportunity to learn from them. You may ask, “Why would and how do I deny a team its accountability?” Well, by downplaying the seriousness of the failure. By saying it’s not a big deal. Failure to deliver here includes failure to ship on time or a degradation or an outage that impacted customers.

You can’t downplay the importance of a feature when the team fails to deliver, yet make a big deal out of the delivery of the same feature when the team succeeds. The impact of the work doesn’t change based on the success of the delivery.

When a team fails to deliver, hold the team accountable because it is the team’s growth opportunity. It’s the team’s right. Treat the team like adults!

Psychological safety

In 2015, Google published a two-year study that showed psychological safety is the biggest factor in nurturing high performing teams. This is not surprising. Most of us knew this from our experiences performing in front of strangers. Under prepared, we tend to not do as well in front of people we don’t feel safe. Imagine speaking in front of a room full of people. Our nerves will get the best of us. But in front of five close friends we rattle off like a professor even though we barely read past the first paragraph of a research paper.

The reason is quite simple. We’re not afraid to look dumb in front of friends. Fear of sucking is what keeps us from offering up our ideas no matter how good they really are. We self filter ideas if they have the slightest chance of embarrassing us. This is why it’s critical to create a safe environment for a team to excel.

An environment that’s psychologically safe can only be created collectively by the team members. You can’t force it. But you can foster behaviors that lead to a safe environment.

Full trust

To feel safe we need to be able to trust each other. Fully. Dr. Brené Brown discovered the best way to build full trust is to be vulnerable.

Vulnerability is basically uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure.

- Dr. Brené Brown

The phrase Daring Greatly, which is the title of her book, came from Theodore Roosevelt's speech "The Man in the Arena".

It’s not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles or where the doer of deeds could have done them better.

The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly... who at best knows the triumph of high achievement and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly.

We are afraid to be vulnerable because we were taught to be perfect. I know every parent denies this. But when we are praised for our achievements and performance our belief system starts to evolve. We begin to fear how we will look if we failed. We fear making mistakes because we'll look stupid. We fear disappointing people because we didn't meet their expectations. Years of pleasing, performing, and perfecting eventually keeps us out of the arena.

Healthy striving is self- focused: How can I improve? Perfectionism is other-focused: What will they think? Perfectionism is a hustle.

Last, perfectionism is not a way to avoid shame. Perfectionism is a form of shame. Where we struggle with perfectionism, we struggle with shame.

Brene Brown: How vulnerability can make our lives better - Dan Schwable, Forbes

So, go all in. Lay it all out. Hold nothing back. Fuck it. Embrace the risk. Be authentic. Be your true self. Be a success. Be a failure. Be proud. Be ashamed. Turns out people are drawn to vulnerability. Because it takes courage. When you can do this, your team members will be encouraged to do the same. And that is when you have full trust. From here on, ideas flow freely. Tobi Lutke calls this a fully charged trust battery. This is also the point when each team member gains full autonomy.

Radical candor

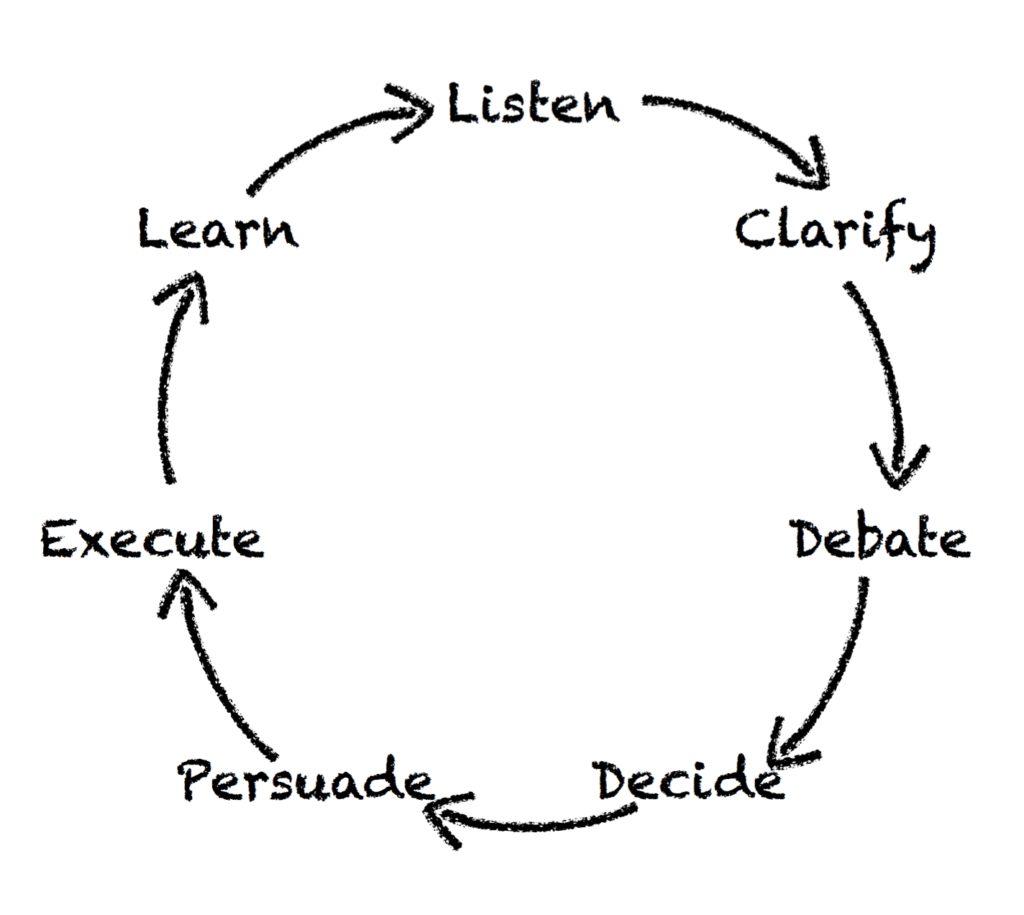

But full trust only facilitates the flow of unfiltered ideas. Ideas are worthless if we can't critique them. Because then, we can't poke holes in an idea and improve it. For the best ideas to surface, we have to be able to give feedback without hurting feelings. Challenge an idea from the opposite standpoint to strengthen the foundation the idea is built upon. But this isn't easy. People have egos. Feedback given the wrong way bruises ego. And this causes conflict. Then we see the ugly side of each other. From giving feedback on an idea to giving feedback on the behavior of a teammate, we need to be what Kim Scott calls radically candid. When debating ideas, she recommends the Get Stuff Done (GSD) wheel.

- First, listen to the idea. Refrain from interrupting. Hold any opinions. Just listen. Intently.

- Next, clarify the idea for you and your team members. Repeat what you heard to make sure you fully understood what was said.

- Debate the idea. Here, practicing Conscious Leadership to understand whether you're above the line or below the line helps you focus on the idea rather than your ego of needing to be right.

- Collect feedback from participants and stakeholders. Let the decision maker make her decision.

- After the decision is made, broadcast the decision. Even if you disagree, commit. Help persuade others to go along with the decision.

- Execute relentlessly.

- Hold a postmortem to assess the result. Learn from mistakes so we can improve.

When providing feedback, Kim recommends the Situation, Behavior, Impact model developed by the Center for Creative Leadership. Be specific when describing all three. The example from Radical Candor is so good, I'm just going to quote it here.

In other words, don’t just say, “You’re aggressive.” Better to say, “In the meeting we just had when you and Zan got in an argument (situation), putting your face three inches from Zan’s and yelling ‘Fuck You’ (behavior) was too aggressive.” Here you are describing the situation and the behavior, but you didn’t describe the impact. Best to say, “In the meeting we just had when you and Zan got in an argument (situation), putting your face three inches from Zan’s and yelling ‘Fuck You’ (behavior) could result in his bringing a lawsuit against the company for allowing a hostile work environment (impact).”

Give humble feedback - Radical Candor

Learn tirelessly

An elite team is never satisfied with the status quo. There is always room for improvement. The team jumps at every opportunity to learn. It's not uncommon to see a team hold a discussion about an article someone read over the weekend. Across teams, members form guilds to share knowledge, code, tools, and best practices. Lunch-and-learns or brown bags are a common scene. So are hack days and game days.

There is one telltale sign of an elite team: they learn in public.

Some of the best engineering teams publish postmortems in the public. These postmortems contain detailed sequence of events that led to degradation or outages that impacted customers. In them, the authors also identify root causes, shortcomings in existing processes and designs, and even what may seem like neglect or incompetence. (But it's important to realize that system failures due to neglect or incompetence are the result of a conscious trade-off made when the system was put in place. When we chose to rely on human judgement or operation of a part of the system over relying on an engineered safety mechanism, we have effectively bet on the humans not making a mistake. But this is a topic worthy of a lengthier discussion for another day.) At the end of the postmortems are usually plans to address the root causes uncovered to minimize the chances of future recurrence of such events. Postmortems are opportunities to learn and improve. But making the postmortems public not only highlights the maturity of the engineering organization, it also gives a chance for the public to learn vicariously. What a gift! With some luck, the team may even be rewarded with feedback from readers who have lived through and successfully tackled similar problems.

Another way I've seen an elite team learn in public is by sharing their work in the form of Request for Comments (RFCs) company wide. RFC is a very effective technique to force clarity of thought. When I write an RFC, I end up questioning a lot of my assumptions. To prove or disprove my assumptions, I have to conduct research and cite evidence. This can either further strengthen my arguments or highlight gaps in my knowledge. Once I broadcast the RFC, feedback from colleagues challenge my thinking in areas that I may have never thought of as potential weak points. When colleagues provide feedback in writing, they too have to cite convincing evidence to persuade me. The result is a highly efficient way to produce well thought out ideas. A big benefit of RFCs is the audience is not limited to a select few. This is important because diversity of opinions is what makes an idea whole. We have no clue Karla spends her nights and weekends reading distributed system papers. Had we not broadcasted the RFC, we'd have missed her insights.

If you have been paying close attention, there's one common thread across all learning activities: writing. You can read blogs, articles, and books. But the most effective way to learn is to write. If you read an interesting article, write the salient points to share with team members. If you read a book, summarize what you read to internalize the concepts and share with your team. If you resolved an outage, write the postmortem and publish it. If you learned about a more efficient design pattern, write a slide deck and do a lunch-and-learn.

Having the balls to look silly because we misunderstood a concept and yet the humility to learn from our mistakes when a teammate points it out are what makes us vulnerable, builds trust, creates a psychologically safe environment and makes an elite team.

Next week, I'll write about the culture of elite teams.