When it comes to choosing the right team size, most folks I've spoken with seem to know the natural upper bound. Perhaps this is due to the popular phrase "two-pizza team" coined by Jeff Bezos.

If a team couldn't be fed with two pizzas, it was too big.

- Jeff Bezos

Unfortunately, Bezos didn't say whether it's a medium size pizza or a large. A medium 12" pizza feeds 3 - 4 people. A large 14" pizza feeds 3 - 5. But, we don't need to be precise here. We can safely say beyond 10 people, someone's going to feel hungry. This is probably where the natural upper bound came from for most.

But, is what Bezos said true?

According to the late J. Richard Hackman, the Edgar Pierce Professor of Social and Organization Psychology at Harvard University, one of the five conditions for a great performing team is team structure. A good team structure is defined by:

- a stable team membership (team membership is not in flux so team members can gel)

- a clear, challenging, consequential direction for the team (well defined areas of responsibility with real risks and rewards that empower the team)

- a right-sized, heterogeneous team (6 - 9 team members who don't always think alike because conflict spurs excellence)

My rule of thumb is that no work team should have membership in the double digits, and my preferred size is six.

- J. Richard Hackman

Hmm... Doesn't that sound like Bezos' two-pizza rule? But why 6 - 9?

...our research has shown that the number of performance problems a team encounters increases exponentially as team size increases

- J. Richard Hackman

Cost of coordination

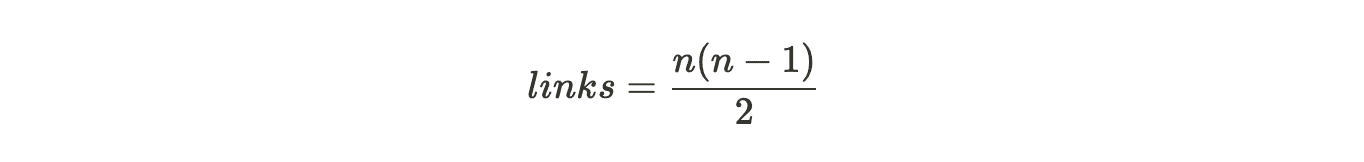

Turns out the exponential increase in performance problems is due to the cost of coordination. The more people you have the more links between them.

A quick illustration:

- A team of 8 has 28 links

- A team of 10 has 45 links

- A team of 12 has 66 links

- A team of 16 has 120 links

With more people in a group, it takes more time and effort to get on the same page. It takes even longer to get buy-in.

If a team gets large enough, the Ringelmann effect starts to set in. In the 1890s, Maximilien Ringelmann was a French agricultural engineer that discovered a phenomenon where the magnitude of an individual's contribution to completing a task decreases as the size of a group increases. This is illustrated in a tug of war.

[Ringelmann] made people pull on ropes separately and in groups, and he measured and compared how hard they pulled. After collecting the results he realized that members of a group tended to exert less effort in pulling a rope than did individuals alone.

The more people on the rope, the lower the performance of each person because of their tendency to feel their own effort is not critical. This loss of motivation to perform is also known as social loafing.

In my post about building a culture, I told the story of Kitty Genovese. It taught an important lesson – diffusion of responsibility.

That is, a person is less likely to take responsibility for action or inaction when others are present. The story teaches us the importance of having accountability.

One way to counter the effects of social loafing is to assign clear accountabilities to each individual. But in a large team, it's near impossible to carve up areas of responsibilities for each individual if the task isn't big enough. And if you attempt to do so, you start getting too prescriptive by creating silly rules in order to "improve" performance.

After a near-death experience from a trip with his colleague, Victor Vroom, J. Richard Hackman was discussing the experience with Vic. Vic was impressed by how the flight crew reacted. The engine fire light came on during the flight and the captain had discharged the fire extinguisher and proceeded to land at the nearest airport. The fire warning turned out to be false. But the aircraft was grounded until the discharged fire bottle was replaced. This was a city where the airline had no service. So, there was no ground crew to help out. The flight crew promptly organized themselves and within hours had arranged meals and lodging for everyone on board.

But, when asked about the experience with the on-board service before the emergency, Vic replied, "I guess it was routine. Nothing really memorable."

How is this possible? The same flight crew that self-organized during the emergency could deliver such an inconsequential inflight experience. The reason, J. Richard Hackman found, was there were so many rules that govern how inflight service must be provided that the crew's sense of excitement had worn off. The rules stifled – nay, extinguished – any creativity the crew had to improve the service. But faced with the emergency and no rules to tell them what to do, the crew flourished.

The bigger the teams, the more rules are needed to exert control, the less context is provided, the poorer the performance.

So, what's clear is large teams perform poorly.

Manager capacity

Each team typically has a team lead or a manager. The individual that answers for the team's performance. The team size is therefore constrained by the manager's capacity. A manager's capacity is bounded by the number of hours in a day no matter how great the manager is.

One of the most effective activities a manager can perform to improve her team's performance is to run weekly 1:1s with her team members. These 1:1s, if run efficiently, can be done in 30 minutes or less. At 6 team members, the manager is spending 3 hours a week on 1:1s. At 8 team members, she's spending 4 hours. Still manageable in addition to her other duties such as removing roadblocks, coordinating across teams, hiring, and coaching. Once you get to 12 members, she's effectively spending one day every week on 1:1s. She's bound to fall behind on something. She either has to sacrifice her focus on something else or her focus on her team members.

You may argue a team of experienced engineers won't need a manager to do much. That is true if this team of experienced engineers have been working together for a while and have gelled. Even with a team that has gelled, there's room for improvement through coaching.

Proper coaching can grow a team from being manager-led to self-organizing. A self-organizing team determines how best to achieve its objectives and baselines. The team knows how to prioritize tech debt and toil against feature work. Because of the autonomy given to the team, they hold themselves accountable for the outcome and consequences of their decisions. But it takes time mentoring and coaching individual team members to get there. An overburdened manager will almost certainly put off coaching when she's short on time. Even though it should be the last thing she gives up on because a self-organizing team will actually free up more of her time.

An example of a self-organizing team is the Edge Engineering team at Netflix. The team of 80 engineers (as of 2018) build and operate over 50 applications.

Our developers are empowered to quickly troubleshoot and fix any production problem on their own. Despite all this, Edge Engineering has zero test teams and zero dedicated operations teams.

- Greg Burrell

The Edge Engineering team operates under the full cycle developer model. That is, the developer is responsible for all areas of the software lifecycle.

Redundancy and burnout risks

People often posit a small, experienced team can outperform a full-sized team. This is true to some extent. A highly experienced team has the depth in knowledge of its domains, the skills to tackle the problems efficiently and the abilities to perform the tasks better than most.

But, too small a team, and you'll find you lack redundancy in certain roles. On a team of 3, John, a subject matter expert of the device authentication & authorization domain may be the only person on the team who knows the domain well enough. The other 2 may have expertise in other domains with no one else who has time to provide redundant coverage for each others' domains. What happens when John is on vacation and one of the device authentication shards failed to replicate to the EU region? Even if nothing is failing, the lack of redundancy will result in a stall in progress for John's tasks because no one else can continue where he left off.

Small teams (<4) are not teams. I've sponsored quite a few 1-2 person teams, and each team I've regretted it. To repeat: I have regretted it every single time.

- Will Larson

A similar situation can manifest itself in the form of an inherited, poorly architected system that is fraught with mines in places you'd least expect. It'll take time even for an experienced senior engineer to uncover the mines and remove them. But before he could get to all of them, he may have burnt out from the constant firefighting.

Nowadays, most high performing teams in a SaaS environment operate what they build. This means team members participate in on-call rotations to provide first-line support for their services. On-call duties can be highly stressful and draining. Each team member can only put up with so much beating before he calls it quits. So, it's imperative that every team member gets a long enough break between each rotation.

Each rotation consists of primary and secondary duties. In a weekly rotation, a team member may be on primary on one week and secondary on the subsequent week. But on a team of 4, each team member has to be on call 2 out of 4 weekends in a month! And these are two weekends in a row. To afford a month-long break between rotations, a team of 8 is required.

Oncall rotations want 8 engineers. For production oncall responsibilities, I've found that two-tier 24/7 support requires eight folks. As teams holding their own pagers has become increasingly mainstream, this has become an important sizing constraint, and I try to ensure every engineering team's steady state is eight folks.

- Will Larson

When Greg Burrell, Sr SRE at Netflix, gave his talk on the full cycle developer on the Edge Engineering team, an interesting exchange took place:

Man 1: And question, one of the downsides of working in operations is where sometimes you have to work on weekends. So does it mean now that everyone at Netflix sometimes has to work on weekends?

Burrell: Yes, that's exactly what it means. Our developers, they're responsible for their applications. They own those applications. And that means they have rotations for being on call. So whoever's on call that weekend, that developer might be the person to answer the alerts and to respond to the pages. They get a lot of support from their team members. They can get a lot of support from the tooling. But ultimately, it's an individual developer who will go in and fix those problems. You'd be surprised how many Netflix outages and problems I've fixed from my couch in my pajamas on the weekends at 2:00 a.m. with maybe my cat beside me. And you think, "Well, some companies, they have these huge rooms that look like NASA mission control and they've got all kinds of graphs and people and it's really hard to get in." But at Netflix, it might just be fixed by a developer in their pajamas on the couch. It's a trade-off. Yes, you do have to work some weekends, but you have a real sense of power and control as well.

This presumably didn't sit well with most folks in the audience. Until a woman asked a follow-on question to clarify.

Woman 2: Could you define some weekends?

Burrell: Well, our teams, as I mentioned, our teams are staffed adequately. So your time in the rotation may not come around for a while.

Woman 2: Okay. So it is a rotation. It's not every weekend.

Burrell: Yes, exactly.

When we size our teams, don't be apathetic to the sacrifice the engineers have to make on weekends when they go on duty. Even when nothing happens, their weekends are lost because they have to clear their weekends of other plans so they are prepared to respond in a timely manner. As a matter of fact, legally time on-call is considered work.

Team make-up

In general, there are two types of engineering teams: feature teams and infrastructure teams. Feature teams build product features and infrastructure teams build infrastructure and tooling that support feature teams. This is a common org design applied at Netflix and Spotify.

Feature teams can be configured a couple of ways. One way is to have feature teams own backend services that provide the feature functionalities via APIs. You then have application team build the frontend that uses the backend services. The second way is to have frontend engineers be a part of the feature teams. In other words, the feature teams own the entire vertical from frontend to backend. Both ways work.

And both have tradeoffs to consider. The first way with the application team places a cognitive burden on the application team to understand all the different features because the application is where all the features come together. But the benefit is a more seamless application. The second way allows a feature team to move independent of other feature teams, as fast as they wish. All coordination takes place within the feature team. However, the resulting application may exhibit seams as the different features come together to make up the application.

I personally prefer the cross-functional team comprised of backend, frontend and test engineers. This minimizes the cross-team dependencies when developing a feature. One way to address the seams at the application is to have a holistic UI/UX design and a common component library.

The idea of having an infrastructure team is to build technical leverage. A central infrastructure team builds common tooling infrastructure that increases productivity of the feature teams.

At Netflix, we have centralized teams that develop common tooling infrastructure to solve the problems that every development team has. Our centralized teams also have specialists in areas such as storage or security or AWS infrastructure. You know, for example, we don't expect all our developers to become deep security experts. But we do have central teams that can provide that security expertise and consult with us. We have central teams that can provide tooling that encapsulates security best practices. In this way, our central teams really become force multipliers.

- Greg Burrell

Within the infrastructure teams, you may have specialized teams that have expertise in different areas such as data, messaging, compute, and developer tools. There is a very good reason for this.

The first one is tooling. I've said it before. I'll say it again. Tooling is key. We need tooling that's easier to use. Our developers, they don't have the bandwidth to become experts on some really complex tooling. We need tooling that's opinionated, tooling that encapsulates best practices, tooling that reduces risk, eliminates toil, lowers cognitive overhead.

- Greg Burrell