In my last post, I wrote about the right and wrong reasons to do a reorg. Once you have decided to do a reorg, the next step is to determine how you can measure progress towards your goals. I first heard about starting a reorg by identifying how to measure success from Will Larson. It makes a lot of sense. If you’re going to make such impactful changes, why wouldn’t you measure how well you did? Why wouldn’t you hold yourself accountable for the decision you made?

Measuring success

For any goal to be meaningful, it has to be defined clearly before changes are made. Because then you’d have a baseline to compare against. Defining the goal after the fact would be akin to drawing the target around the arrow.

When defining goals, we all know to ensure they are specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-based (SMART). But the typical SMART goal doesn’t cut it here. The reason is a SMART goal is missing two critical components:

- Baseline - A baseline allows anyone with minimal understanding of the goal to quickly determine how well you’re doing against the goal by simply comparing the current measurement against the baseline or how meaningful is your goal by comparing the target with the baseline.

- Trend - A trend provides the current direction of a metric. This helps folks understand the urgency and importance of meeting the goal, especially if the trend is headed in the wrong direction. Otherwise, the trend will continue. The historical trend also indicates the level of difficulty to achieve the goal.

I highly recommend reading Will Larson’s piece on defining meaningful goals.

So, how do we decide what to measure in a reorg? Because goals for reorg vary, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all metric. But I can think of some examples. If your goal is to improve the customer experience by making your product seamless, one metric might be the number of clicks to get to your destination.

You could also conduct a survey to measure the reaction before and after the reorg. If your goal is to improve productivity through more efficient communication following the reorg, you might use some of Accelerate’s metrics.

The point is to determine the metric to measure before the reorg. Take a measurement of the current state as the baseline. Then, fully define your goal:

In Q2, the number of clicks to get to the dashboard of any product will decrease from 4 to 1. In Q1, the number of clicks increased from 3 to 4.

Recall above a goal needs to be not only SMART but also have a baseline and a trend. The baseline here is 4 clicks. The progression in Q1 shows an upward trend of increasing clicks.

Now that you have a goal to track against, it’s time to choose an org structure.

Functional vs Divisional (Unit)

In doing something big at scale, the organization influences, and even determines, much of what gets built. As a CEO or big company executive, organization is one of the very few things that is entirely your doing and responsibility.

- Steven Sinofsky

There are two main ways to structure organizations: functional and divisional (or unitary). In a functional org, you have people organized around their functions or expertise. That is, within a functional org, you would have functions such as sales, marketing, finance, HR, engineering, legal, and so on. On the other hand, a divisional org is organized around products or business units.

Conglomerates such as Berkshire Hathaway, Icahn Enterprises, and Constellation Software are some examples of the closest to pure divisional orgs. The holding company avoids operational activities because it lacks expertise and manpower. Besides, meddling in the operations of its subsidiaries would run counter to the very definition of a holding company. Alphabet is perhaps the least known conglomerate with the best-known subsidiary, Google. Alongside Google are standalone businesses such as Access (which includes Google Fiber), GV (formerly Google Ventures) and CapitalG (formerly Google Capital).

Most large organizations are divisional usually due to the breadth of products they offer. Microsoft is one such example. Today MS has three divisions or segments: Productivity and Business Processes (Office 365, LinkedIn), Intelligent Cloud (SQL, GitHub, Azure), and More Personal Computing (Windows, Xbox, Surface).

The best known large functional organization is Apple. Apple does this for a very specific reason: to optimize for seamlessness. That is, the entire org is a single division. With a singular focus on the best user experience through design. This has been the sole focus for Apple since Steve Jobs return in 1998. The reason for this strategy is Apple believes the differentiation in design is what makes Apple unique. Untouchable. In its own class. Apple products work seamlessly together. (But sometimes they can take their clean design sentiment a little too far, e.g. Magic Mouse 2 that's unusable while charging 🙄) No other companies can offer the same breadth of products with the same design and experience.

We think we have the right architecture not just in silicon, but in our organization, to build these kinds of products.

- Steve Jobs

But Apple's success can also be its greatest enemy. The functional org is a huge advantage when it comes to building seamless products. However, it's an anchor when it comes to building services. And this shows in Apple’s services. iMessage is probably one of the biggest missed opportunities. It could have been WhatsApp. If only Apple stuck with the same motto since 1998: Think different. But apply it within. That is, instead of making it seamless with Apple devices, make it seamless with all devices. Or maybe they did think differently. WhatsApp started in 2009 and had demonstrated the growth that came from supporting communication between iPhones, Nokias, and BlackBerries. iMessage didn't launch until 2011. And they still didn't support non-iPhones. Fast forward to 2019. Despite iMessage's 1.3 billion users due to iPhones sold, WhatsApp (now part of Facebook) overtook iMessage with 1.5 billion users. We're now in 2020. iMessage still doesn't work with Androids. Meanwhile, WhatsApp announced on Feb 12, 2020, they have reached more than 2 billion users. You can lead a horse to water, but you can't make him drink.

Despite Apple's missed opportunities, it is still the most valuable company in the US ranked by market cap. Microsoft is a close second. Functional or divisional, they both work. But functional works for Apple because of Apple's uniqueness.

When we say a company has a functional org or a divisional org, we're really referring to the org structure at the peak. Below the peak, the org could be organized completely opposite to its peak.

Purity in org structure makes for great caricatures of orgs, but operationally rarely exist.

- Steven Sinofsky

Types of Org Structure

Most org structures are variations of functional or divisional orgs. Let's examine the types of org structures available and their pros and cons.

Functional Org Structure

The functional org structure groups individuals by their functions. The groups form departments. Some functions such as legal, finance, and HR naturally fall into this sort of org structure. These functions are usually corporate functions that are common across the company.

Pros

- There are clear roles, responsibilities, and lines of command.

- The functional focus encourages development of deep expertise within the function due to the tighter collaboration among functional members.

Cons

- The narrow focus of each function can result in silos.

- The line of command can take precedence over collaboration between departments.

- There isn't a clear Directly Responsible Individual (DRI) for a project or product. Some organizations assign a Product Manager or a Program Manager (à la Microsoft) as the DRI that will ensure the delivery and success of a project.

Apple is the best known example of a large functional org. They came up with DRIs to address the issue of a lack of accountability.

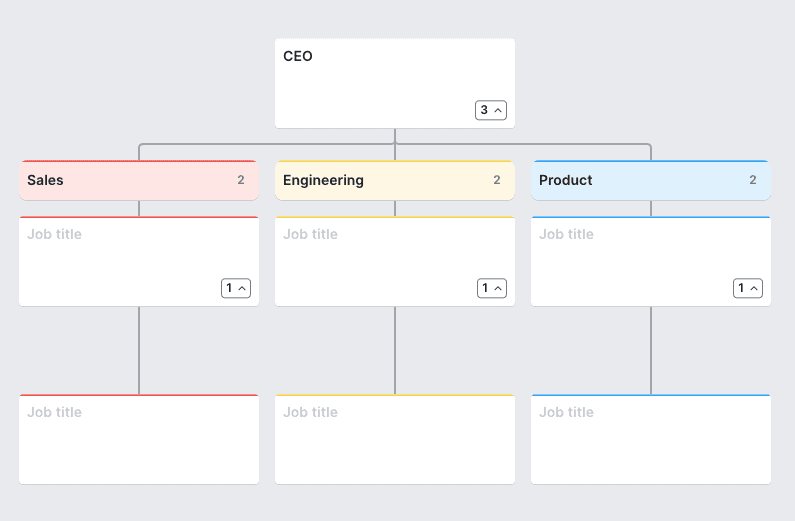

Divisional - Product Org Structure

In a product divisional org structure, individuals are organized by product. Here's the kicker: beneath each product, you likely have a functional suborg. So, you can think of this as really just a multiple of functional orgs under one roof. But each functional org is dedicated to a product (can be one or more related products).

Pros

- There's one neck to choke for each product division.

- There are clear roles, responsibilities, and lines of command.

- Each product can move independent of another, potentially increasing speed of iteration. For example, cloud based services iterate a lot faster than hardware products.

Cons

- Lack of cross-pollination of knowledge across products can lead to silos and duplicate efforts.

- Dedicated resources under each product division can discourage cross-product collaboration. Rather it encourages fierce rivalry when it comes to resource claims, especially shared resources.

Microsoft is an example of a product divisional org. Comprised of three segments that provide business products and services, enterprise cloud software and services, and consumer software and products.

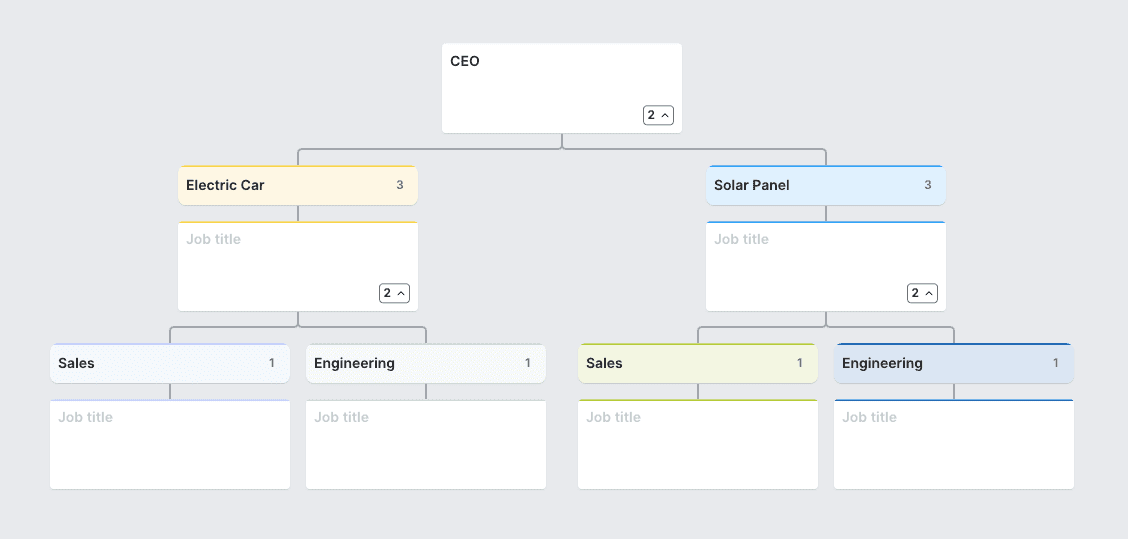

Divisional - Market Org Structure

Market divisional org structures are well suited for companies that serve multiple markets that require different types of products and services. By segmenting the markets, each division can develop distinct sales, marketing, and product strategies to best serve the segment. Like the product divisional org structure, a market divisional org shares many of the same pros and cons.

Pros

- There's one neck to choke for each market division.

- There are clear roles, responsibilities, and lines of command.

- Each market division can offer distinctive products and services for the market it serves.

Cons

- Lack of cross-pollination of knowledge across markets can lead to silos and duplicate efforts.

- Dedicated resources under each market division can encourage fierce rivalry when competing for shared resources.

Banks like JPMorgan Chase are typically organized by market segments: corporate and consumer. Corporate customers have very different needs ranging from payroll and retirement plans to underwriting services. Consumers, on the other hand, need checking and savings accounts, and credit cards.

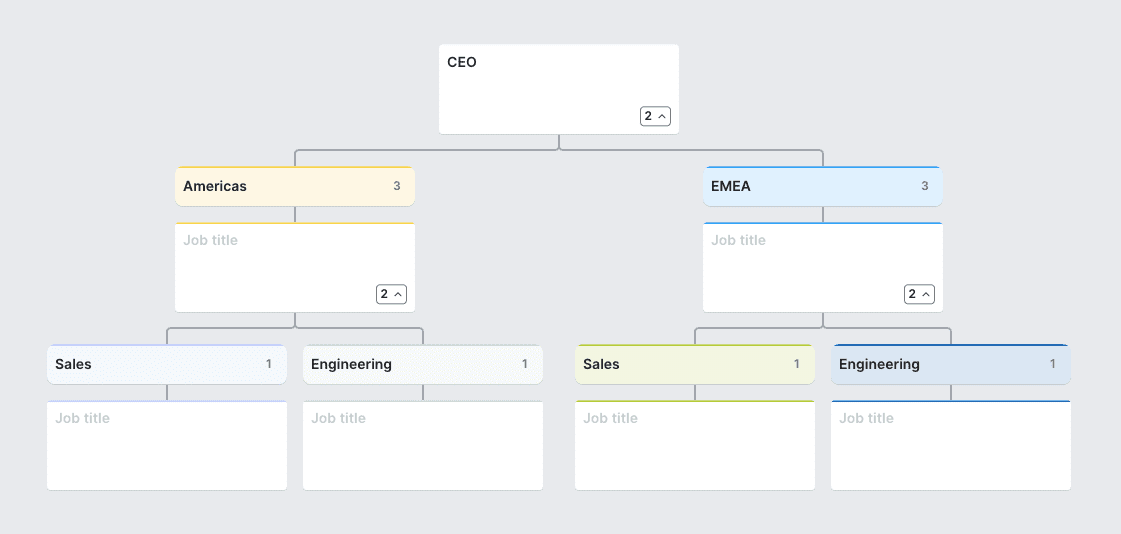

Divisional - Geographic Org Structure

Companies with a global footprint usually end up with a geographic divisional org structure. This is most prevalent in companies with products that are regulated or require different go-to-market strategies for different regions.

Pros

- There's one neck to choke for each market division.

- There are clear roles, responsibilities, and lines of command.

- Each geographic division can develop a distinct go-to-market strategy for the geographic region it serves.

Cons

- Lack of cross-pollination of knowledge across geographies can lead to silos and duplicate efforts.

- Dedicated resources under each geographic division can create a hostile corporate environment due to competition.

Automotive companies such as Honda, Toyota, and Ford tend to be geographically organized because they depend on efficient sourcing of parts for assembly. Also, in some countries, foreign ownership of domestic entities is restricted (Qatar restricts foreign ownership of listed companies to 49%). Having a geographic division allows the division to get acclimated to the local environment and policies.

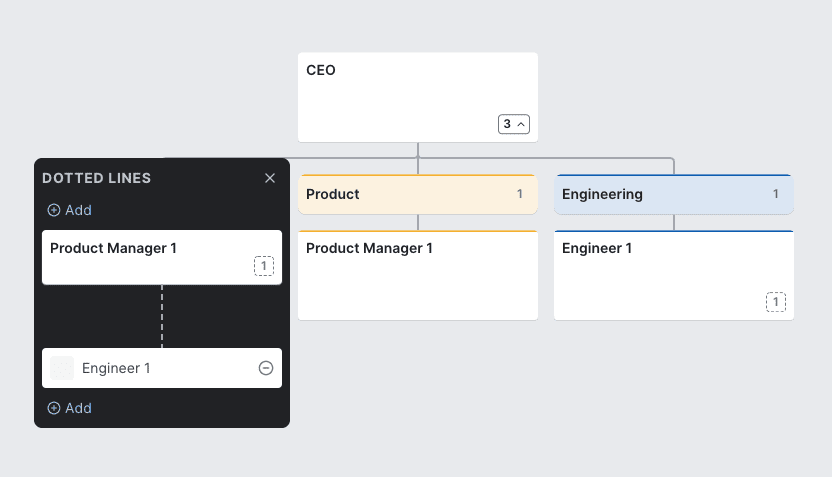

Matrix Org Structure

84% of orgs were matrixed to some extent according to a Gallup survey of 4,000 employees in 2015 . In fact, this was predicted back in May 1978 in a Harvard Business Review article titled Problems of Matrix Organizations.

We believe that in the future matrix organizations will become almost commonplace and that managers will speak less of the difficulties and pathologies of the matrix than of its advantages and benefits.

In a matrix org, people with the same function report up to a functional manager. But they also dotted-line report to a product manager. The problem is the dotted line relationship is fictional. People respond best to the folks who set their pay.

Pros

- Employees have both functional responsibilities and product responsibilities.

- Cross-functional teams collaborate on the same product minimizing silos.

Cons

- The presence of two axes of reporting lines creates both confusion about responsibilities and a power struggle between the product and functional manager. The confusion and power struggle lead to a complete dysfunction of a product team.

- Without clear definition of responsibilities and authority over decisions, a matrix product team can succumb to navel gazing. If decisions need to be surfaced to the functional manager for clearing, team members are effectively blocked.

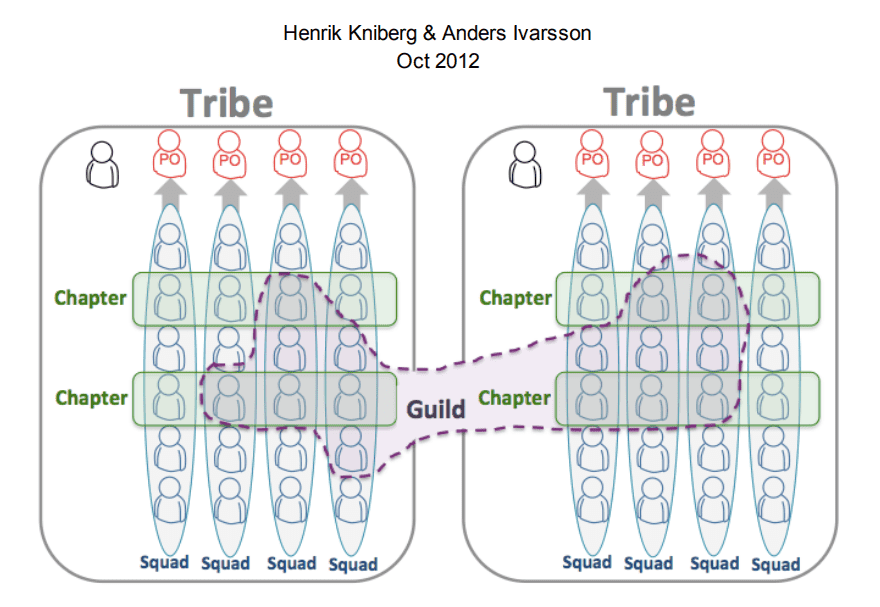

Given the problems that come with the matrix org, why is it so seductively popular? It's because the pros outweigh the cons. And the cons can be solved. One company that took the traditional matrix org, flipped it on its head and made it wildly successful is Spotify.

Source: Spotify Scaling

Unlike the traditional matrix, Spotify made the decision authority explicitly clear by rotating the matrix at a right angle. This is very similar to a scrum team. A squad has all necessary constituent roles to function autonomously. The best way to think about a squad is to imagine it is a mini-startup. The product owner is the CEO. The mini-startup builds one or more features and services. The team members in a squad still report to their respective functional managers. The functional managers help provide coaching, mentorship, and a clear career growth path. The engineering manager is accountable for the squads delivery and operations. The product owner is accountable for the feature design, planning, scheduling, and prioritization.

Spotify's way is not the only way to address the shortcomings of a matrix org. But the idea of full autonomy and accountability given to each squad is what makes it so attractive and successful.

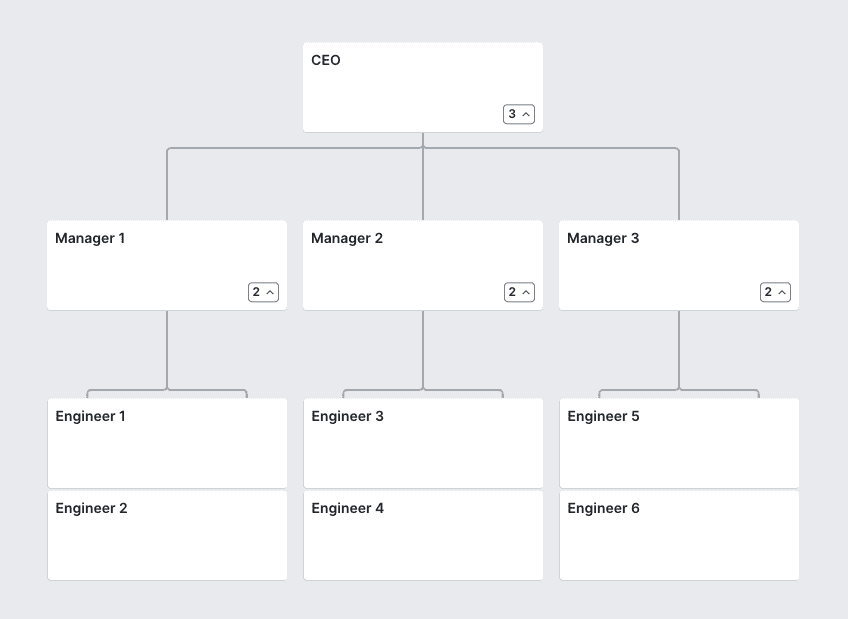

Flat Org Structure

Decisions are made rapidly in a flat org structure because individuals are given full autonomy to do what's best for the company. This org structure is also the most popular among early-stage startups. Early on, the manager layer could be completely non-existent, in which case, all engineers report to a single manager (up to the managers' capacity). This structure is also the most effective for shipping quickly. It is this stage of life of a startup that is the most rewarding and fondly remembered.

Pros

- Individuals are not only entrusted but also expected to make high impact decisions.

- Responsibilities are so broad they can span other functions. But this is also what excites the team members.

Cons

- This structure doesn't scale very well beyond hundreds of employees because it is challenging to coordinate large initiatives that span multiple teams without clear accountability.

- When a tiebreaker is needed, information needs to be surfaced to the CEO for a final decision, drastically slowing down decision making.

- Unless career paths are clearly defined, as the company grows employees may be confused about how they can advance in their careers.

There are two highly successful companies I know that operate with a flat structure: Basecamp (maker of Basecamp) and Valve (maker of Half-Life and Counter-Strike). Basecamp is currently at 50 employees. Basecamp's enviable product and no-bullshit, simple, yet highly productive culture won them a massive following of admirers. Their employee handbook appendices lay out the titles and responsibilities for each career path. There are leads or managers on each team to drive projects to completion and handle the people management aspect. Because of the small team size, the individual team members are expected to be self-directed more so than in a typical organization setting.

Valve has 360 employees. Their products need no introduction. More intriguing is how, in the absence of no managers, a group of over 300 managed to produce hit after hit. Valve also publishes its somewhat hilarious employee handbook. Valve has an interesting setup that stemmed from their experience building their first hit, Half-Life.

In the end, we came to the conclusion that this ideal person [godlike game designer] didn’t actually exist. Instead, we would create our own ideal by combining the strengths of a cross-section of the company, putting them together in a group we called the "Cabal."

Employees are grouped into cabals or teams of 12 or more people. Each cabal is responsible for designing and building parts of a game. Team members move their desks on wheels to the cabals they want to join. But not all is rosy at Valve. In 2013, former employee, Jeri Ellsworth, said in a podcast:

"It is a pseudo-flat structure where, at least in small groups, you're all peers and make decisions together," she said. "But the one thing I found out the hard way is that there is actually a hidden layer of powerful management structure in the company and it felt a lot like high school. There are popular kids that have acquired power in the company, then there's the trouble makers, and everyone in between."

Richard Geldreich, another former Valve employee, took to Twitter to express his frustration with self organizing companies. One of his tweets appeared to confirm the favoritism Jeri mentioned in her interview.

At self-organizing firms you might be placed into a huge open office and given massive monitors. This is to normalize all communications and for more effective surveillance. Everything will be monitored either directly by a corporate arm employee, one of their barons or friends.

— Richard Geldreich (@richgel999) July 16, 2018

There is even a term used to jokingly refer to the game releases from Valve: Valve Time – the difference between the promised release date and the actual release date.

GitHub ran as a flat org until it reached 600 employees. They cited the following reason:

...a flat organization compromised its ability to get things done.

After they switched to a traditional hierarchical org, they realized coordination by the heads of engineering, legal, marketing, sales, and other departments has been crucial to recent achievements.

The largest company that still runs as a flat org is W. L. Gore, the company best known for its weatherproof Gore-Tex fabrics. The company with over 9,500 employees uses a flat org structure called the lattice organization, developed by Bill Gore in 1967. Today, the lattice organization principle is known as open allocation. A similar concept to cabal used at Valve.

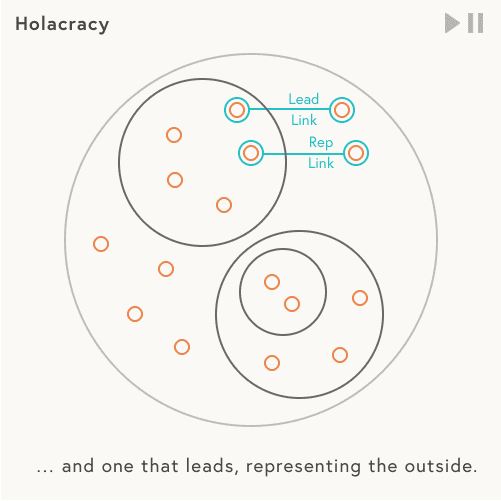

Holacracy

Source: Holacracy, Explained

Holacracy is a form of a flat org structure with carefully defined constructs to help companies navigate the issues that can arise from pure flat org structures. Most companies that begin as a flat org structure transition into a more traditional hierarchical org structure once they reach a manager's capacity. Assuming a CEO can manage 8 managers and each manager can manage another 8, a flat org structure can handle up to 8 x 8 = 64 people excluding the CEO before another layer of management needs to be introduced.

At a high level, a holacracy org is made up of a company circle with circles within (similar to departments). Each circle can have one or more sub-circles. Each circle has one or more roles. Each role has a defined purpose, a set of domains and accountabilities. It’s important to note a role is not a person. A person can have multiple roles, even unrelated ones. Each circle has a lead link who leads the circle and represents the outside, and a rep link who represents the circle to the outside.

Pros

- Decisions are pushed to self-organizing teams so that they can be made as fast at possible. No need for running a decision up a flagpole.

- Individuals are truly empowered (through authority bestowed on the role) to make decisions and take actions that are believed to be aligned with the purpose outlined for the role.

- There is no confusion about the accountabilities of each individual because they are fully defined by the role(s) of the individual.

- Holacracy constitution describes in detail how the org should self-govern and run. This eliminates confusion and disarray that typically arise from the less formal flat org structure.

Cons

- The misuse of circles by layering sub-circles with different individuals holding different roles in the sub-circles can end up recreating the very bureaucracy holacracy is meant to eliminate.

- Gaining alignment for large scale initiatives is difficult due to a lack of hierarchy especially when it requires coordination across many circles. This is a challenge even in traditional hierarchy.

- The holacracy constitution is complex. There are a lot of rules to learn in order to function effectively in a holacracy org. Bud Caddell, a management consultant who advised Zappos on their holacracy rollout said, "The average employee is already overworked and undertrained; asking them to learn the management equivalent of Dungeons and Dragons on top of their workload is foolish, if not inhumane."

- The vast majority of talent today don't have experience working at a holacracy org. The misconception of holacracy propagated by the media may cause talent to avoid holacracy orgs. This could lead to challenges in recruiting.

- The lack of a feedback mechanism traditionally carried out by managers in holacracy org presents a problem when it comes to improving performance of individuals. Radically candid feedback and one-on-one sessions are the most effective tools to improve individual performance.

- Because an individual can play multiple roles, even unrelated roles, career progression and compensation become murky. How should you pay someone who writes code and designs marketing strategy?

The best known large company that has a holaracy structure is Zappos which has about 1,500 employees. Medium had reportedly somewhere between 50 and 150 employees at the time it gave up on holacracy.

After Zappos implemented holacracy, 150 departmental units evolved into 500 circles.

This doesn't mean the org became more complex. It means the departments were refined further into smaller, finer circles.

Zappos has twice as many “lead link” roles as it had managers pre-holacracy.

But remember, these are roles. Not individuals. The same individual can have multiple roles. There is, however, a real cost to having lots of microroles.

At Zappos, each of the 7.4 roles an individual fills contains an average of 3.47 distinct responsibilities, resulting in more than 25 responsibilities per employee.

With so many roles and responsibilities, employees struggled with prioritizing work and coordinating across circles.

Choosing your org structure

With so many options, how do you decide which is the right org structure for your org? Go back to the reason you wanted to do a reorg to begin with. In fact, it's the second of the three Golden Rules of Re-Orgs laid out by Steven Sinofsky.

Golden Rule of Re-Orgs — Know the problem you are solving. If there is one thing that consistently amazes me it is that org changes are made without clearly and deliberately identifying what problems will get solved by the new structure, new leaders, and new resource allocation.

- Steven Sinofsky

The first rule, also the one everyone knows about, was highlighted in my last post:

Don't ship the org chart.

- Steven Sinofsky

Identify the org structure that will best address the problem you're trying to solve. Like everything else, there will always be tradeoffs. Unfortunately, there is no "right" answer.

Often there is no "correct" answer to how to structure your organization, rather it is a series of tradeoffs. Two different structures may be equally "good" and "bad". Don't sweat it too much - ultimately if you make a mistake it is painful but you can undo it.

- Elad Gil

But, you can at least measure success or failure if you determined how to measure success before you embark on your reorg.

Like software architecture, when designing your org choose the simplest org structure that will solve your problem. No point overcomplicating structures and introducing unnecessary processes to compensate for the structural complexity. Go with what's known. Avoid mental overload.

Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.

- Albert Einstein

Last but not least, the most important of Sinofsky's three Golden Rules of Re-Orgs:

Golden Rule: Ship schedule is everything. I intentionally saved this for last because it is the only point in here that I don’t believe is a pendulum, a grey spectrum, or contextual. The most important thing to consider in org design is that when it comes to execution, collaboration, and alignment ship schedule is everything.

- Steven Sinofsky

Software that runs on client devices usually has a less frequent ship schedule – typically monthly or longer. Contrast this to SaaS which can be updated multiple times a day with minimal impact on customers. If you have a product comprised of both client-side and server-side software, you'll come to a crawl if you structure an org that binds both teams to the same release schedule. However, it is critical to align the ship date. Otherwise, the product will never make it to customers in one piece. So, when structuring your org, concentrate the maximum number of decisions under the domain of a designated manager to coordinate across teams in order to successfully release a product or a feature.

Every org structure has weak points. Superman's weakness is kyrptonite. Cybertruck armour glass' weakness is a metal ball.

Identify the paths that you did not optimize – As important as picking the communication paths that you will optimize is identifying the ones that you will not. Just because you de-prioritized them doesn’t mean that they are unimportant. If you ignore them entirely, they will surely come back to bite you.

- Ben Horowitz

Once you made the tradeoffs, don't forget them. Have a plan to mitigate the issues that can arise due to the tradeoffs.

Next up, we'll look at how we should size teams.